Based on the latest electoral boundaries released by the Electoral Boundary Review Committee (EBRC), we have done a follow-up analysis for the upcoming General Elections.

Under the new electoral boundaries, the challenges of representativeness remain. Since winning the general election in Singapore requires the right geographical distribution of seats won in addition to the popular vote, a political party with sufficient candidates and a strong enough party machinery in key constituencies has a strong structural advantage. This gives the PAP a distinct leg up, given its nationwide presence, numerical superiority in candidates, and advantage in party resources. A so-called “freak” election where the PAP loses power is highly unlikely, even improbable, with the new electoral boundaries.

By the same reasoning, non-PAP parties are almost just as unlikely to win even the one-third of seats needed to block constitutional changes even if they win well more than a third of the popular vote.

With the new boundaries, it is still possible to form the next government with 23.8% of the popular vote, maintain a simple parliamentary majority with 26.9% of the popular vote, and obtain a constitution changing two-third supermajority with 31% of the popular vote. In comparison, winning the one-third of seats needed to block a constitutional change requires a minimum of 16.1% of the popular vote, but non-PAP political parties can fail to win this number of seats even with 67.7% of the popular vote. Likewise, a party can win up to 75.2% of the popular vote, but fail to win the 45 seats needed to form the next government. These results depend on the geographical distribution of votes across the various constituencies.

Consequently, being able to form the next government is marginally more difficult for smaller political parties this election compared to the last, but it is easier for a larger political party to win a two-thirds supermajority. It is also meaningfully more difficult for smaller political parties to win one-third of parliamentary seats this election compared to the previous one, given the need to win both across more constituencies and a larger share of the popular vote than before. This will be more demanding on resources.

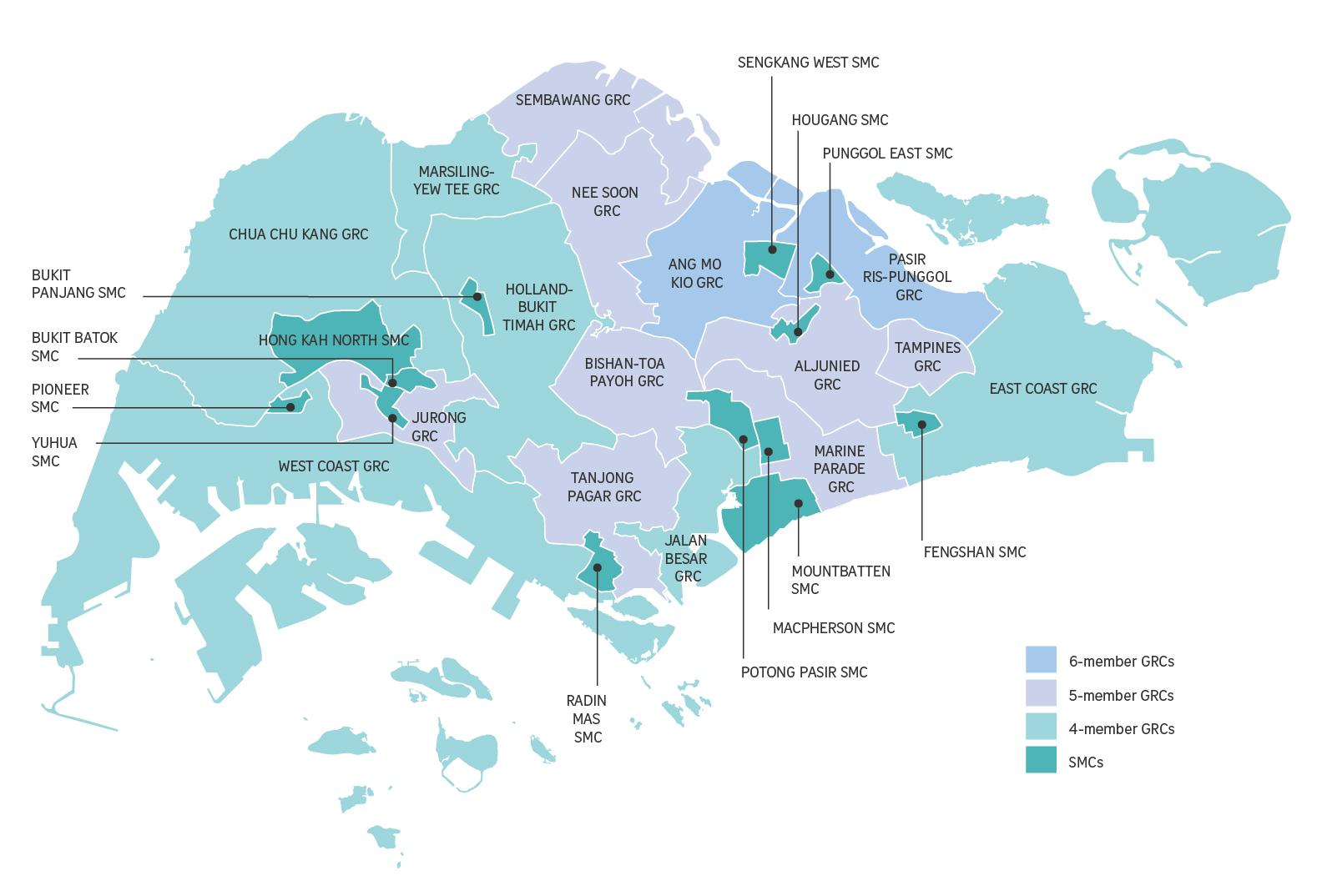

To form a new government with a simple majority of 45 out of 89 contested seats, a political party must win 23.8% of the popular vote, all five four -GRCs (Choa Chu Kang, East Coast, Holland-Bukit Timah, Jalan Besar, Marsiliing-Yew Tee, West Coast), and the four smallest five-member GRCs (Bishan-Toa Payoh, Jurong, Nee Soon, and Tanjong Pagar).

The new ruling party can lose every other vote available for contest.

In GE2011, forming the government meant winning a minimum of 23.8% of the popular vote, the two four-member GRCs (Holland-Bukit Timah, Moulmein-Kallang), six of the smallest five-member GRCs (Bishan-Toa Payoh, East Coast, Jurong, Nee Soon, Tanjong Pagar, West Coast), and the smaller of the six-member GRCs (Ang Mo Kio). A political party now has to win a minimum ten GRCs to form the next government compared to nine in GE2011.

Assuming that Parliament retains its Non-Constituency Member of Parliament (NCMP) and Nominated Member of Parliament (NMP), a political party must win at least 26.9% of the popular vote and an additional five of the smallest SMCs to have a simple Parliamentary majority of 51 seats. These would be Bukit Batok, Fangshan, Hong Kah North, MacPherson, Mountbatten, Pioneer, Potong Pasir, and Yuhua. This assumes that Hougang is not in play. The winning party does not have to win any additional votes. A simple majority allows the ruling party to pass laws without hindrance, assuming that our political parties maintain the practice of only allowing MPs to vote freely with the lifting of the party whip.

To reach a simple majority in the upcoming elections, a political party has to win at least five SMCs over the number of seats needed to form the next government as compared to one SMC and one five person GRC beyond the number of seats needed to form government in GE2011.

Winning the constitution changing two-thirds majority, or 59 seats out of 89, means that a party just has to win 31% of the popular vote, down from 31.4% in GE2011.

However, the party must also win the next smallest five-member GRC (Tampines), and the six smallest SMCs (Bukit Batok, Fangshan, Hong Kah North, MacPherson, Mountbatten, Pioneer, Potong Pasir, Radin Mas, and Yuhua—assuming Hougang stays out of play) on top of the constituencies mentioned in the second paragraph. The winning party can lose every single vote in the remaining constituencies. This is a total of 17 constituencies compared to 15 in GE2011. NMPs and NCMPs cannot vote over constitutional amendments.

To win more than one-third of the seats in Parliament necessary to block a constitutional amendment, a political party has to win a minimum of 16.2% of the popular vote, all the SMCs, three of the smallest four-member GRCs (East Coast, Jalan Besar, and West Coast), and one five-member GRC (in this case, we assume it is Aljunied).

To reach the same one-third threshold in GE2011 a political party had to win at least 15.1% of the popular vote, the two smallest five-member GRCs (Bishan-Toa Payoh, East Coast) in addition to Aljunied, both four-member GRCs (Holland-Bukit Timah, Moulmein-Kallang), and six of the smallest SMCs (Hougang, Joo Chiat, Mountbatten, Potong Pasir, Yuhua) in addition to Ponggol East. The party and its allies need not win any additional vote.

In the end, this means to assure one-third of Parliamentary seats, the new boundaries require a win in at least 18 constituencies compared to 13 in GE2011.

The largest win a political party can get but still fail to form the next government is 75.2% of the popular vote. That translates into winning every single vote in the larger of the two six-member GRCs (Ang Mo Kio), seven of the eight five-member GRCs excepting Aljunied, and the three largest SMCs (Bukit Panjang, Radin Mas, Sengkang West). The same party receives 50% less one vote in each of the other constituencies. This will get a political party 44 seats out of 89.

In contrast, a political party can be unable to secure one-third of Parliamentary seats even with 67.7% of the popular vote, the two six-member GRCs, the three largest five-member GRCs (Aljunied, Marine Parade, Sembawang), and two SMCs (assuming Hougang, Ponggol East). This presumes that the party wins every single vote in each of these constituencies, but loses by 50% less one vote in each of the remaining constituencies.

A political party can also win up to 83.3% of the popular vote but fail to secure a two-thirds supermajority if it wins all both six-member GRCs, seven of the eight five-member GRCs excepting Aljunied, the two largest four-member GRCs (Holland-Bukit Timah, Bishan-Toa Payoh), and three of the largest SMCs excluding Ponggol East (Bukit Panjang, Radin Mas, Sengkang West). The same party also loses in every other constituency by 50% less one vote.

Note that this analysis makes several key pre-suppositions. It takes the minimum number of votes needed to win a constituency as 50% of electors in that constituency plus one vote in this analysis, which presumes that the electoral competitions are effectively two-sided. The maximum a party can win in a constituency are the votes of all the eligible electors in that constituency. The analysis further assumes that the current Workers’ Party constituencies are not in play, implying that the Workers’ Party stays in opposition and retain their seats. The analysis assumes that there is no possibility of a minority government. These are reasonable assumptions given the almost overwhelming structural edge the PAP enjoys and the general advantages of incumbency in specific constituencies.

Nonetheless, even putting current WP constituencies, Aljunied, Hougang, and Ponggol East, back into play will not change the fundamental conclusions of this analysis, since it focuses on structural advantages and disadvantages and holds campaign effects constant.

The need to consider both vote share and geographical distribution in the GRC plus SMC electoral system parallels the U.S. presidential system, where candidates and political parties have to consider not just the popular vote, but also Electoral College votes. Electoral College votes are allocated according to the population in each state.

In such a system, it is possible to win the popular vote, but lose the election by having less Electoral College votes. Al Gore and the Democratic Party discovered this reality in 2000 when they lost the presidential election to Republican George W. Bush. The Electoral College system encourages presidential candidates and political parties to focus on “big” states with more electoral votes and their concerns rather than “small” states. If Singapore maintains the GRC plus SMC system, this unequal geographical distribution of attention by political parties is likely to take place when elections become meaningfully competitive across Singapore.

To conclude, the structural advantages that the current electoral boundaries and Singapore’s electoral system give to the PAP mean that a changeover in government is virtually impossible in the upcoming election. Non-PAP parties gaining the one-third of seats necessary to block any constitutional changes are just as unlikely. Any fundamental change to Singapore’s electoral politics will have to wait until a non-PAP party or some collection of parties have a serious nation-wide on-the-ground, grassroots presence, or if the PAP for some reason loses this presence across the island. Non-PAP parties should focus on winning specific seats in the short-term, but develop a nationwide presence in the longer term.

In other words, there will be more heat than light this upcoming election. Particular election battles will be hard fought as non-PAP parties try to gain more GRCs and the PAP tries to hold on to them while attempting to retake Aljunied.

At the end of the day, the PAP will most likely retain its parliamentary dominance this upcoming election. This means to say that voters who wish to support non-PAP parties should feel free to do so. After all, the PAP is unlikely to be able to withhold benefits to a large proportion of Singaporeans spread across the island even if it is the ruling party.

In fact, the PAP will likely be more responsive to voter concerns if it retains its parliamentary advantages with alower share of the popular vote, given its desire to limit any further bleeding of votes in subsequent elections. There are few repercussions from voting non-PAP this upcoming election and even a few advantages.

Analysis of the Electoral Boundary below. (Information from Election Department)

Note: Colored cells represent the constituencies that must be won for the different scenarios