A year ago this weekend Wayne Rooney stood at Manchester's equivalent of Checkpoint Charlie, ready to throw himself into the arms of City. In the tense preceding days, 40 figures in balaclavas gathered at the Rooney residence to warn him he was passing into darkness.

United are rarely seen in desperation mode, but 12 months back Old Trafford was convulsing. With Cristiano Ronaldo in Madrid, Rooney was the English emblem a new team was being shaped around. In previous eras Alan Shearer said no thanks and Paul Gascoigne had weaved his way to Spurs. But Rooney was captured and converted, for £27m, in August 2004. As City closed in, United felt like Everton six years earlier, but without the need for money.

Rooney will lead United's attack in what Sir Alex Ferguson calls the biggest Manchester derby of his 25 years in charge. This week the pugnacious one struck his 25th and 26th Champions League goal to overtake Paul Scholes's record of 24 for an Englishman. By Thursday, he was being touted as the leader of Great Britain's Olympic football team. Even the Kop looked on him kindly. The most scathing chant they could come up with in last Sunday's north-west derby at Anfield was: "Who's the scouser in the wig?"

The 40 hooded men take no credit for the U-turn. Though Rooney was said to be spooked by their presence outside his gates, ghoulish threats were not the cause of his volte face. The wounding insult delivered to United in the form of a statement questioning the club's "ambition" two hours before a Champions League tie against Bursaspor appeared designed to detonate a terminal rift. In the game fans held up a banner calling him a "whore" and declared: "Coleen forgave you. We won't."

When the shock wore off, Ferguson and David Gill went to work, inserting a wedge between Rooney and his agent and alerting the Glazer family to the risk that their most high-profile player was about to high-tail it across town.

Rooney's contract was due for renewal in the summer of 2012. His intention was not to leave in some general sense but to join City, who were prepared to award him a pay rise of more than £100,000 a week. As United players testified later, the first tactic was to persuade him he was making a crashing error, and that he had become a slave to his agent, Paul Stretford, a notoriously ice-blooded negotiator.

Ferguson's press conference on Rooney's inflammatory statement has passed into legend. It was a classic of simultaneous persuasion and coercion. Reciting the values of his club Ferguson was wounded and defiant as he cast the struggle as a question of honour. "We've done everything we can for Wayne Rooney since the minute he came to the club," he said. "We've always been there as a harbour for him."

Outside the club, football lined up behind Ferguson. "He needs to remember where he came from," Mark Lawrenson, a Liverpool icon, said of Rooney. All the while United faced the imminent threat that the player would follow Carlos Tevez from red to sky blue and tip the power balance in favour of Sheikh Mansour and his scheme to construct a sporting fantasia in one of the most deprived districts of Manchester.

Moral obligation was the smaller of two levers. It was the conference call with the Glazers and subsequent whopping pay rise that sent Rooney back to the red Carrington to apologise to his team-mates, where Patrice Evra was especially scathing in his condemnation of his team-mate's arrogance in demeaning recent acquisitions. Rooney was a United player again, contrite but also richer. No longer nagged by the thought of a rainbow curving down to Eastlands, he resumed the hard climb back to his old barn-burning form.

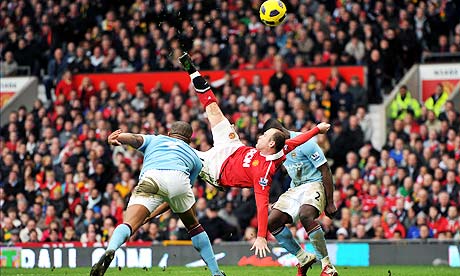

With his combustible nature, and part shy, part belligerent make-up, there is no stop Rooney has failed to make on his eventful journey to physical maturity. In the 12 months since United broke their own wage structure to keep him, his occasional gift for Brazilian ingenuity has expressed itself with a wonder goal (the bicycle kick) in last season's Manchester derby at Old Trafford while his reckless volatility has blown a major hole in England's chances of winning Euro 2012.

The overhead kick described by Ferguson as the most brilliant goal he had seen at Old Trafford evoked the one that helped persuade United to buy him in the first place. "Our under-nine side played Everton's boys one day and they absolutely hammered us," Paul McGuinness, United's academy manager, says. "Rooney scored a few [six], but there was one that stood out. It was basically the classic overhead kick, the perfect bicycle kick, which for a kid of eight or nine years old was really something special."

"Devastated" by his three-match Uefa ban, according to Ferguson, Rooney now carries his 158 goals in 332 appearances for United into a derby he might have jogged into from the away dressing room. Next weekend brings a trip to his alma mater, Everton, where he seldom appears comfortable trying to bite the first hand that fed him.

For United's supporters, footage of the aerial spin that bamboozled City's defenders cannot be shown too often as the opposition prepare to roll out Sergio Agüero, David Silva and Samir Nasri. Ferguson has tried to negate City's spending power through youth cultivation and selective strikes in the transfer market: Phil Jones, Chris Smalling, David de Gea, Ashley Young. But the biggest riposte was hanging on to a player United already possessed, in those volcanic days when Ferguson may have felt he was losing control of a star player for one of the very few times in his career.

There was always an acceptance that Ronaldo would return to Iberia one day. Roy Keane, David Beckham and Ruud van Nistelrooy, on the other hand, were pretty much expelled. This time, though, the team's primary match-winner was threatening to pack his case and walk straight through Checkpoint Charlie. Without that conference call, Rooney would have been the Agüero in City's XI.