Sarikei 1964-1965: Indonesian Konfrontasi

-

Extracted from the ‘Indonesian Confrontation 1964-1965’ (*1)

In 1964, Indonesia launched a campaign of confrontation against the newly-created Federation of Malaysia, seeking to de-stabilise and ultimately to destroy it. Most incursions were into Sarawak and Sabah, with a few into mainland (Western) Malaysia.

Dawn 'stand-to', 3 RAR, Sarawak - 1964

The Malaysian Government requested the commitment of Australian troops to Borneo in January 1965, resulting in 3RAR and 102 Field Battery (then with the BCFESR), 1SAS Squadron and a number of field and construction squadrons being deployed to Borneo. Further, 111 Light Anti Aircraft Battery, relieved later by 110 Battery, was deployed to the Butterworth Air Base in Western Malaysia in case of Indonesian air attack.

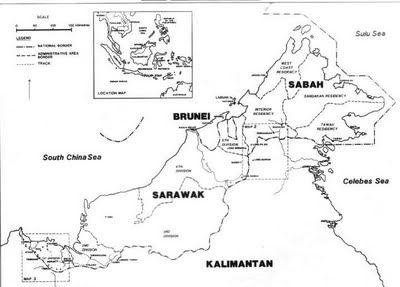

This map shows Sabah, Brunei and Sarawak on the Malaysian side of the border and Kelimantan on the Indonesian side.

In the meantime, several brigades of Indonesian regular troops had been moved from Java to Kalimantan, opposite Sarawak and Sabah. Ultimately 22,000 regular Indonesian troops including 12 infantry battalions , 4,000 irregulars and 2,000 Clandestine Communist Organisation (CCO) operatives with some 24,000 Chinese sympathisers, were involved. The Indonesian incursions into Sarawak and Sabah were in relatively small groups, often less than platoon-level.

By the end of that year, there were 21 British, Gurkha and Malaysian battalions, with supporting arms, deployed in Borneo.

The Commonwealth security forces were deployed primarily in company bases within mutually supporting gun range, patrols being mounted to secure intelligence, set ambushes and to force the Indonesians to remain behind their own border. 3RAR served on operations from March to July 1965, and 4RAR April to August 1966. 1SAS Squadron served from April to August 1965 and 2SAS Squadron from March to July 1966.

As well as operations on Borneo and the mainland of Malaysia, Australian troops, mainly from the Pacific Islands Regiment, were engaged in intensive patrolling along the only land border between Indonesia and Australian territory – in Papua New Guinea. While there was only one shooting incident, the demands of patrolling in such difficult terrain imposed a considerable drain on the available pool of Australian officers and NCOs.

Confrontation formally ended in August 1966. Australian Army casualties were seven KIA, six WIA, with 10 non-operational deaths and 14 non-operational other casualties

Commonwealth Forces Foot Patrol - 1964

The CLARET Operations

The operations always retained a high level of secrecy. When 3 RAR arrived it had to patrol on the Malaysian side of the border for a mandatory period of one month before it could begin Claret Operations.

The incursions into mainland Malaysia in the latter half of 1964 brought Indonesia and Malaysia (with its British and Australian allies) close to war, and in September some British planners talking of conducting sea and air strikes against Indonesian bases. Instead. Walker was authorised to conduct operations up to 5000 yards (4570 metres) across the Indonesian border. The strictest secrecy was observed and the 'Claret' operations, as they were known, were aimed at ambushing Indonesian troops and supply parties as they moved towards the border. By the end of the year Walker had eighteen British battalions (including eight Gurkha and two Royal Marine Commandos) and three Malay battalions in Borneo. Also at the end of the year he was given permission to extend his operations up to 10 000 yards (9140 metres) across the border.

- The 'Golden Rules' for Claret operations were as follows:

- Every operation to be authorised by DOBOPS [Walker].

- Only trained and tested troops to be used.

- Depth of penetration to be limited and the attacks must only be made to thwart offensive action by the enemy.

- No operation which required close air support-except in an extreme emergency-must be undertaken.

- Every operation must be planned with the aid of a sand-table and thoroughly rehearsed for at least two weeks.

- Each operation to be planned and executed with maximum security.

- Every man taking part must be sworn to secrecy, full cover plans must be made and the operations to be given code-names and never discussed in detail on telephone or radio.

- Identity discs must be left behind before departure and no traces-such as cartridge cases, paper, ration packs, etc-must be left in Kalimantan.

- On no account must any soldier taking part be captured by the enemy-alive or dead.

These rules were later eased, but the operations always retained a high level of secrecy. When 3 RAR arrived it had to patrol on the Malaysian side of the border for a mandatory period of one month before it could begin Claret operations.

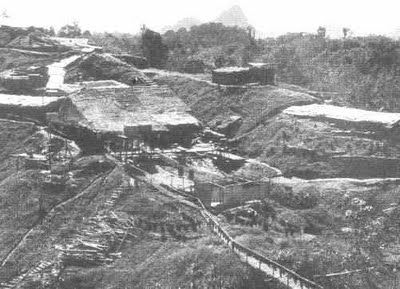

Commonwealth Forces - Patrol Base - 1964

B Company 3 RAR was located at a place called Bukit Knuckly - which was described as a cross between a part of a WW-1 trench system, and an American Wild West Fort. They made successful raids across the border. These were not reported in the Press, and the death toll was never mentioned by the Indonesian Government. Secrecy was strict on both sides.

During Konfrontas (1962-1966), 114 members of the Commonwealth Forces, 36 Sarawak civilians, and 590 Indonesian troops were killed.

During the Communists' armed struggle (1965-1973), 190 communists wre killed in Indonesia and 340 in Sarawak.

- The 'Golden Rules' for Claret operations were as follows:

-

‘The Military Experience – Confrontation with Indonesia 1964 - 1965’ (*2)

The first Claret raids were shallow affairs carried out by superb Gurkha troops and the SAS. The SAS participated in the raids since it knew better where the Indonesians were and could guide the Gurkha units to their objectives.

The SAS, permitted to run its own four-man raids, was gleeful about the chance to do something other than "watching and counting." The SAS nicknamed itself "The Tiptoe Boys" because of its ability to strike the enemy hard and slip away, leaving only empty space to receive the enemy counterattack.73

Infantry raids still assumed larger proportions (up to company size) than SAS raids, but they remained small enough to avoid precipitating a violent Indonesian response. As the risks were great, so were the precautions: "no rifleman was allowed to eat, smoke, or unscrew his water bottle without his platoon commander's permission.

At night, sentries checked any man who snored or talked in his sleep. Whenever the company was on the move, a reconnaissance section led the way, their packs carried by the men behind."74

Appearing ghost like out of the jungle, these parties of light infantrymen usually achieved complete surprise. After conducting a trail or river ambush or an early-morning attack on an Indonesian border post-forward base, the Gurkhas immediately returned to the friendly side of the border. Pursuing Indonesians had to take care to avoid being caught in an ambush.

As time passed, more and more of the experienced infantry battalions were given permission to participate in Claret operations. Walker also increased the depth of penetration from 5,000 yards to 20,000 yards. Ultimately, the operations accomplished their goal: the frequency of enemy offensive actions in Borneo fell off as the Indonesians became preoccupied with protecting themselves.

Throughout the war, the British never acknowledged their raids into Kalimantan territory. The Indonesians, on their part, were embarrassed too much by the raids to make a political issue of them.

Tactical Issues

The tactics, combat support, and individual skills required by the British in Borneo resembled those practiced by their light infantry in Malaya. Nevertheless, because three years had elapsed since the struggle in Malaya, the troops initially deployed to Borneo required extensive acclimatization to the jungle climate and retraining in jungle warfare. As in Malaya, infantry units received their training at the Jungle Warfare School, where they rapidly reacquired the necessary skills.

Significant differences did exist, however, between the tactical style of operations used by the British in Borneo and that in Malaya. Owing to the larger size of the threat in Borneo (the Indonesians rarely moved in groups smaller than a platoon), the British infantry generally operated more at the platoon level than at the squad level. In addition, because the enemy fought more tenaciously in Borneo, the British devoted more attention to conservation of ammunition. Isolated patrols could not afford to run out.

Light infantry attacks in Borneo most often took the form of ambushes. These ambushes, as in Malaya, lasted for long periods of time. One infantry unit, for example, maintained an ambush in waist-to-shoulder-deep water for three days, rotating the men on the ambush site every ninety minutes. 75

In Borneo, the infantry conducted more river ambushes than they had in Malaya. The sparse settlement in Borneo also permitted the British to set up remote ambushes using claymores and other mines-ambushes that were self-detonated by the victims.

Occasionally, these mines were triggered by animals. However, even if the Indonesians did not fall victim to these remote ambushes, their nondetonation informed the British that no enemy patrol had passed that way.

Close-air and artillery support were used more widely in Borneo than in Malaya, mainly because the Indonesians presented better targets. To support local patrolling, 105-mm howitzers were deployed into jungle bases singly and in pairs.

Using these widely separated pieces was not easy, however, because of the difficulty in controlling indirect fires. Infantry NCOs had to be proficient in calling for fires, since they seldom had forward observers along. Similarly, each gun section had to have the capability to compute firing data. In addition, a special fire-control net was established. In view of the extraordinary requirements of the situation, the artillery command in Borneo published special, area-specific SOPs. 76 The RAF conducted no bombing operations in Borneo.

Logistics

The greater difficulty of the terrain, the lack of a decent road net, the wider decentralization of forces, and the improvements in helicopter technology and techniques influenced the British to provide 90 percent of their logistic effort in Borneo by air.

The British also employed watercraft in resupplying units. The Hovercraft, in particular, was put to good use, carrying both troops and cargo via inland waterways. Watercraft, unlike helicopters, could also operate at night.77

Owing to its precarious situation, the SAS supplied itself by placing caches here and there for emergency use. It also supplemented its light rations with jungle foods such as fruits, bamboo shoots, animals, and other local fare. The jungle could have sustained the SAS completely, but such an approach would have consumed too much of its time. The standing requirement for SAS teams on patrol was to be able to vanish for two weeks without having to resurfacefor resupply. 78

Weapons and Equipment

The mild controversy over weapons and equipment that was generated during the Emergency grew in intensity during the Confrontation. Walker considered that none of the available standard infantry weapons was satisfactory. 79

The issue rifle (SLR) was too long and heavy for use in the jungle. Troops much preferred the AR-15, the export version of the U.S. M-16. Its lighter ammunition (5.56-mm) and high velocity seemed much better suited to their situation than the slower, 7.62-mm NATO round. Shotguns, once again, demonstrated their great utility for close fighting in heavy vegetation.80

The British reevaluated their use of other weapons. The aging, but highly regarded, Bren gun was in the process of being withdrawn from the inventory during the 1960s, but its replacement, a belt-fed medium machine gun was deemed too heavy and too susceptible to malfunction from dirt and water.

In the 1950s, the ATOM manual declared that the 2-inch mortar had no utility in the jungle; nevertheless, in Borneo, the 81-mm mortar was thought to be too heavy for patrolling, and units preferred the 2-inch mortars. Its reduced range posed no problem in the close quarters of jungle warfare. 81

Walker complained to his suppliers that many other items of equipment weighed too much for light infantry work. He identified tactical radios, airground radios, jungle clothing, and rations as items requiring lightening.

-

This third piece of records of the past historical events will provide the political background to the military conflicts, and the various strategies employed by a smaller force facing the challenges posed by a larger military force in unfamiliar terrain.

An abstract from

‘Indonesia – Malaysia Confrontation’ (*1)

British forces in Borneo included Headquarters (HQ) 3 Commando Brigade in Kuching with responsibility for the western part of Sarawak, 1st - 4th Divisions, and HQ 99 Gurkha Infantry Brigade in Brunei responsible for the east, 5th Division, Brunei and Sabah. These HQs had deployed from Singapore in late 1962 in response to the Brunei Revolt. The ground forces comprised some five British and Gurkha infantry battalions normally based in Malaya, Singapore and Hong Kong and rotated with others and an armoured car squadron. In the middle of 1963 Brigadier Pat Glennie, normally the Brigadier General Staff in Singapore, arrived as Deputy DOBOPs.

The naval effort, under DOBOPS command, was primarily provided by minesweepers used to patrol coastal waters and larger inland waterways. A guardship, a frigate or destroyer, was stationed off Tawau.

The initial air component based in Borneo were detachments from squadrons stationed in Malaya and Singapore. These included Twin Pioneer and Single Pioneer transport aircraft, probably two or three Blackburn Beverley and Hastings transports, and about 12 helicopters of various types. One of Walker’s first ‘challenges’ was curtailing the RAF’s centralised command and control arrangements and insisting that aircraft tasking for operations in Borneo was by his HQ, not by the RAF’s Far East HQ in Singapore. Other aircraft of many types stationed in Malaya and Singapore provided sorties as necessary including routine transport support into Kuching and Labuan.

The police deployed a number of paramilitary Police Field Force companies.

At this stage Indonesian forces were under command of Lieutenant General Zulkipli in Pontianak, on the coast of West Kalimantan about 200 km from the border. The Indonesian irregulars, led by Indonesian officers, were thought to number about 1500 with an unknown number or regular troops and local defence irregulars. They were deployed the entire length of the border in eight operational units, mostly facing the 1st and 2nd Divisions. The units had names such as Thunderbolts, Night Ghosts and World Sweepers.

However, in the East, opposite Tawau and on the Indonesian half of Sebatik Island were five companies of the Indonesian Marines (Korps Komando Operasi - KKO) as well as a training camp for volunteers.Pocock p. 176British tactics

Soon after assuming command in Borneo General Walker issued a directive listing the ingredients for success, based on his experience in the Malayan Emergency:

*Unified operations (army, navy and air force operating fully together);*Timely and accurate information (the need for continuous reconnaissance and intelligence collection);*Speed, mobility and flexibility;*Security of bases;*Domination of the jungle;*Winning the hearts and minds of the people (this was added several months later).

British jungle tactics were developed and honed during the Malayan Emergency against a clever and elusive enemy. They emphasised travelling lightly, being undetectable and going for many days without resupply. Being undetectable meant being silent (hand signals, no rattling equipment) and ‘odour free’ – perfumed toiletries were forbidden (they could be detected a kilometre away by good jungle fighters), and on occasions food was eaten cold to prevent cooking smells.

In about 1962, at the end of National Service, British infantry battalions had reorganised into three rifle companies, a support company and an HQ company with logistic responsibilities. Battalion HQ included an intelligence section. Each rifle company comprised 3 platoons each with 32 men, equipped with light machine guns and self loading rifles. Support company had a mortar platoon with 6 medium mortars (3 inch mortar until replaced by 81 mm mortar around the end of 1965) organised into 3 sections, enable a section to be attached to a rifle company if required. Similarly organised was an anti-tank platoon, there was also an assault pioneer platoon. The machine gun platoon was abolished, but the impending delivery of the 7.62 mm GPMG, with sustained fire kits held by each company, was to provide a medium machine gun capability. In the meantime Vickers machine gun remained available. The innovation in the new organisation was the formation of the battalion reconnaissance platoon, in many battalions a platoon of ‘chosen men’. In Borneo mortars were usually distributed to rifle companies and some battalions operated the rest of their support company as another rifle company.

The basic activity was platoon patrolling, this continued throughout the campaign, with patrols being deployed by helicopter, roping in and out as necessary. Movement was usually single file, the leading section rotated but was organised with two lead scouts, followed by its commander and then the remainder in a fire support group. Battle drills for ‘contact front’ (or rear), or ‘ambush left’ (or right) were highly developed. Poor maps meant navigation was important, however, in Borneo the local knowledge of the Border Scouts compensated for the poor maps so tracks were sometimes used unless ambush was considered possible, or there was the possibility of mines. Obstacle crossing, such as rivers, was also handled as a battle drill. At night a platoon harboured in a tight position with all-round defence.

Obviously a contact while moving was always possible. However, offensive action usually took two forms: either an attack on a camp or an ambush. The tactic for dealing with a camp was to get a party behind it then charge the front. However, ambushes were probably the most effective tactic and could be sustained for many days. They targeted tracks and, particularly in parts of Borneo, waterways. Track ambushes were close range, 10–20 metres, with a killing zone typically 20–50 metres long, depending on the expected strength of the target. The trick was to remain undetected when the target entered the ambush area and then open fire all together at the right moment.

Fire support was limited for the first half of the campaign. A commando light battery with 105 mm Pack Howitzers had deployed to Brunei at the beginning of 1963 but returned to Singapore after a few months when mopping-up the Brunei Revolt ended. Despite the escalation in Indonesian attacks after the formation of Malaysia little need was seen for fire support, the limited range of the guns (10 km), the limited availability of helicopters and the size of the country meant that having artillery in the right place at the right time was challenge. However, a battery from one of the two regiments stationed in Malaysia returned to Borneo in early to mid 1964 these batteries rotated until the end of confrontation. In early 1965 a complete UK based regiment arrived. The short range and substantial weight of the 3-inch mortars meant they were of very limited use.

Gunners from Australian 102 Field Battery

Artillery had to adopt new tactics. Almost all guns deployed in single gun sections within a company or platoon base. The sections were commanded by one of the battery's junior officers, warrant officers of technical sergeants. Sections had about 10 men and did their own technical fire control. They were moved underslung by Wessex or Belvedere helicopters as necessary to deal with incursions or support operations. Forward observers were in short supply but it seems that they always accompanied normal infantry Claret operations and occasionally special forces ones. However, artillery observers rarely accompanied patrols inside Sabah and Sarawak unless they were in pursuit of a known incursion and guns were in range. Observation parties were almost always led by an officer but only two or three men strong.

Communications were a problem, radios were not used within platoons, only rearwards. However ranges were invariably beyond the capability of manpack VHF radios (A41 and A42, copies of AN/PRC 9 and 10), although use of relay or rebroadcast stations helped where they were tactically possible. Patrol bases could use the World War 2 vintage HF No 62 Set (distinguished by having its control panel labeled in English and Russian). But until the manpack A13 arrived in 1966 the only lightweight HF set was the Australian A510, which did not provide voice, only Morse code.Special Forces

One squadron (up to 64 men in total in its four patrol troops) from the UK based 22 Special Air Service deployed to Borneo in early 1963 in the aftermath of the Brunei Revolt to gather information in the border area about Indonesian infiltration. There was a special forces presence until the end of the campaign. Of course faced with a border of 971 miles they could not be everywhere and at this time 22 SAS had only three squadrons, although there was also the Special Boat Service (SBS) that had two sections based in Singapore. Tactical HQ of 22 SAS deployed to Kuching in 1964 to take control of all special forces. The special forces shortage was exacerbated by the need for them in South Arabia, in many ways a far more demanding task in challenging conditions against a cunning and aggressive opponent.

The solution was to create new units for Borneo. The first to be employed in Borneo was the Guards Independent Parachute Company, which already existed as the pathfinder force of 16th Parachute Brigade. Next the Gurkha Independent Parachute Company was raised. Sections of the Special Boat Service were also used, but it seems mostly for amphibious tasks. Finally Parachute Regiment battalions formed patrol companies (C in the 2nd and D in the 3rd). The situation eased in 1965 when the Australian and New Zealand government agreed that their forces could be used in Borneo, enabling Australian SAS and New Zealand Ranger squadrons to rotate through Borneo.

Special forces activities were probably mostly covert reconnaissance and surveillance by 4 man patrols. However, some larger scale raiding missions took place including amphibious ones by the SBS. Once Claret operations were authorised most special forces missions were inside Kalimantan, although they conducted operations over the border before Claret from about early 1964.

3rd Battalion Royal Australian Regiment - soldiers emerging from jungles of Borneo

continued below

-

continue from above

1963

On 20 January 1963, Indonesian Foreign Minister Subandrio announced that Indonesia would pursue a policy of Konfrontasi with Malaysia. On 12 April, Indonesian volunteers—allegedly Indonesian Army personnel—began to infiltrate Sarawak and Sabah, to engage in raids and sabotage, and spread propaganda.

Walker recognised the difficulties of limited forces and a long border and in early 1963 was reinforced with an SAS squadron from UK, which rotated with another mid-year. The problem was that even when the SAS temporally adopted 3 instead of 4 man patrols they could not closely monitor the border. Another way was to increase the capability of the infantry to create a surveillance network.

To this end Walker raised the Border Scouts, building on Harrison’s force of Kelabits, who had mobilised to help intercept the fleeing TNKU forces from the Brunei Revolt, the experience of the Royal Marines, and knowing the skill and usefulness of the Sarawak Rangers in the Malayan Emergency. This was approved by the Sarawak government in May as ‘auxiliary police’. Walker selected Lieutenant Colonel John Cross, a Gurkha officer with immense jungle experience for the task. A training centre was established in a remote area at Mt Murat in the 5th Division and staffed mostly by SAS. Border Scouts were attached to infantry battalions and evolved into an intelligence gathering force by using their local knowledge and extended families. In addition the Police Special Branch, which had proved so effective during the Malayan Emergency in recruiting sources in the communist organisation, was expanded.

Confrontation could be said to have started from a military perspective when the police post at Tebedu was attacked.Dennis (et al) 2008, p. 152. On 27 July, Sukarno declared that he was going to "crush Malaysia" ().

Further small incursions followed, typically attacks on longhouses. In June an operation by about 15 was dealt with. In this period it was a platoon commander's war for the British. Platoons deployed individually in semi-permanent patrol bases, initially in villages but then outside them to reduce the risk to inhabitants in event of an Indonesian attack. Helicopter landing sites were cleared a few kilometres apart all along the border area, and platoons patrolled vigorously. Small parties of Gurkhas, police and Border Scouts were stationed in many remote villages.

On 15 August a headman reported an incursion in the 3rd Division and follow up indicated they were about 50 strong. A series of contacts ensued as 2/6 Gurkhas deployed patrols and ambushes, and after a month 15 had been killed and 3 captured. The Gurkhas reported that they were well trained and professionally led but their ammunition expenditure was high and their fire discipline broke down. The prisoners reported 300 more invaders within a week and 600 in a fortnight.

The Federation of Malaysia was formally established on 16 September 1963. Brunei decided against joining, while Singapore later left the Federation in 1965 to become an independent republic. Indonesian reacted immediately and furiously, tensions rose on both sides of the Straits of Malacca and the Malayan ambassador was expelled from Jakarta. Two days later, rioters burned the British embassy in Jakarta. Several hundred rioters ransacked the Singapore embassy in Jakarta and the homes of Singaporean diplomats. In Malaysia, Indonesian agents were captured and crowds attacked the Indonesian embassy in Kuala Lumpur.

The Battle of Long Jawai was the first major incursion the centre of the 3rd Division. Some 200 Indonesians with 300 porters and longboats moved to Long Jawi, population about 500, some 50 miles from the border. It was a junction for river and track communications. The British outpost in the village was in the process of establishing a new position on a nearby hill, but their communications remained in the village school. The total British force was 6 Gurkhas, 3 Police Field Force and 21 Border Scouts, with a handful in the school and the remainder in the new position.

An Indonesian reconnaissance force had entered the village on about 26 September but their presence was unknown to the British and their main body arrived. At 5:00 am on 28 September 1963—the day Malaysia came into being—the force opened fire with small arms and mortars on the two posts. The communications post was heavily attacked and hit by mortar fire and communications lost without the attack being reported, Gurkha and police radio operators were killed. The fighting lasted four hours, one Gurkha, one policeman, one Border Scout and five Indonesians were killed. Ammunition ran low, and the Border Scouts became demoralised and started to slip away and some were captured but the Gurkhas and police successfully withdrew into the jungle. The Indonesians plundered the village and executed ten of the captured Border Scouts.

The lost communications meant that it took 2 days for news to reach the HQ 1/2 Gurkhas, but reaction was swift and the entire Wessex helicopter force was made available. Helicopters enabled the Gurkhas to deploy ambush parties to likely withdrawal routes in orchestrated action that lasted until the end of October. The tortured bodies of 7 Border Scouts were found. 33 Indonesians are known to have been killed, 26 in a boat ambush on 1 October.

The failure of the Border Scouts to detect the incursion, particularly since the Indonesians were in Long Jawi for 2 days before the attack, led to a change of role. Instead of being paramilitary they concentrated on intelligence gathering. It also emphasised the need for the 'hearts and minds' campaign. However, the Indonesians had lost the trust of the local population, who had witnessed them plunder the village and the executions of the Border Scout Prisoners. The locals had also been impressed with the quick Gurkha reactions. For the rest of the war civilians would inform British forces of Indonesian troop movements they saw.

The creation of Malaysia meant that Malaysian Army units deployed to Borneo (now East Malaysia). 3rd Battalion Royal Malay Regiment (RMR) went to Tawau in Sabah and the 5th to the 1st Division of Sarawak. The Tawau area also had a company of the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry. Brigadier Glennie, who was directly responsible for the East Brigade area had recognised the risks in the area. The RN guardship made a seaborne attack unlikely but the myriad creeks and rivers around Tawau, Cowie Harbour and Wallace Bay were a challenge. He organised an ad hoc waterborne force that became the Tawau Assault Group (TAG).

One of 3 RMR's positions was at Kalabakan west of Tawau. There was a fortified police station and 400 yards away in 2 unfortified huts (with some adjacent fighting trenches) were some 50 RMR soldiers with their company commander. In late December a force of 35 KKO regulars and 128 volunteers crossed into Sabah and remained in the swampland undetected for 8 days. The mission was to capture Kalabakan move on Tawau with Indonesian expatriates rising to join them. At 11:00 pm on 29 December the RMR position had been taken by surprise, with 8 killed including the commander and 19 wounded. An attack shortly after on the police station failed. The attackers moved north instead of east to liberate Tawau. Gurkhas were flown in and after a month it was over. Two thirds of the KKO participants were killed of captured and admitted that they had expected the population to rise and greet them as liberators.

TAG became properly established based on an infantry company, marines and a Naval Gunfire Observation Party from a battery in Hong Kong. They dominated the area, and included a raft-mounted mortar. One of their 'posts' was a boat permanently positioned close to the international border across Wallace Bay. A minesweeper was usually part of TAG because there were no other naval patrol boats suitable for coastal use.continued below

-

continue from above

1964

During the year command arrangements changed. 99 Gurkha Infantry Brigade HQ returned from Singapore and replaced 3 Commando Brigade HQ in Kuching. 3rd Malaysian Infantry Brigade HQ arrived to take over East Brigade in Tawau, and 51 Gurkha Infantry Brigade HQ arrived from UK to command the Central Brigade area with the 4th Division of Sarawak added to it.

Its headquarters was in Brunei and there were no roads to any of its battalions. In DOBOPS all HQ elements were finally concentrated in one HQ complex on Labuan.[21] At least one of the British batteries stationed in Malaysia was always deployed in Borneo with its 105 mm guns.

In summary in about the middle of the year the situation was:

-

- West Bde (HQ 99 Gurkha Infantry Bde), frontage 623 miles, 5 battalions.

- Central Bde (HQ 51 Gurkha Infantry Bde), frontage 267 miles, 2 battalions.

- East Bde (HQ 3 Malaysian Bde), frontage 81 miles, 3 battalions.

Another Malaysian battalion joined East Bde mid-year, and later a third Malaysian battalion, a battery and an armoured reconnaissance squadron.

This brought the total force to 12 infantry battalions, two 105 mm batteries and two armoured reconnaissance squadrons. (For comparison the British Army in Germany had 14 battalions).

The British component of 8 battalions in Borneo was being sustained by rotating 8 Gurkha and about 7 British battalions stationed in the Far East. In addition there were the equivalent of two Police Field Force battalions and some 1500 Border Scouts.[22]

In 1964 British tactics changed. What had been a platoon commanders’ war became a company commanders’ one. Most of the dispersed platoon bases were replaced by heavily protected permanent company bases, mostly a short distance from a village, ideally with an airstrip.

Each normally had a section of two 3-inch mortars and a few had a 105 mm gun, although guns had to be moved to deal with incursions. However, they continued to dominate their areas with active patrolling, sometimes deploying by helicopter, roping down if there was no landing site. When an incursion was detected troops, sometimes relying on the Border Scouts’ local knowledge of tracks and terrain, were deployed by helicopter to track, block and ambush it. The Border Scouts tracking skills were highly valued when pursuing the enemy.[23]

RAF Whirlwind Helicopter - 1964

Support helicopters, RAF Belvedere and Whirlwind, and RN Wessex and Whirlwind, had increased to 40 but it was not enough. Late in the year another 12 Whirlwinds arrived.[21] The RN had adopted forward basing, notably at Nanga Gat in the 2nd Division on the Rajang River, which the RAF had previously declared unsafe for helicopters, but subsequently used as a forward base for Whirlwinds.

At Bario in the 5th Division, RN helicopters received their fuel in air-dropped 44 gallon drums from RAF Beverleys. However, the expansion of the Army Air Corps (AAC) was creating air platoons or troops of 2 or 3 Sioux in many units, including some infantry battalions, which proved very useful. In addition the AAC was operating Auster and Beaver fixed wing aircraft, and some of the new Scouts, which could carry a similar number of troops as a Whirlwind. However, in the remoter areas of Sarawak the Twin Pioneers of the RAF and RMAF were vital, and the RAF's Single Pioneers were also useful. East Bde had the benefit of RMAF Alouette 3s and RNZAF Bristol Freighters were also used between major airfields.

The Indonesian Air Force also operated air transport, particularly into the more mountainous areas of the border that were beyond rivers navigable by larger boats and landing craft. Although they had far less aircraft than the Commonwealth forces, those they had were far more capable. They included the workhorse helicopter Mil Mi-4 NATO reporting name HOUND, the largest helicopter in the world, Mil Mi-6 NATO reporting name HOOK, and C-130 Hercules.

It appears that the Indonesians lost a C-130 in Borneo, but there are various stories about the circumstances. One is that it crashed while avoiding a Javelin. Another has more detail, the Long Bawang airfield is at the base of a small ‘beak’ of Indonesian territory protruding into the 5th Division of Sarawak near Ba Kelalan, RAF fighter patrols along the border had a habit of ‘cutting the corner’ and flying across the ‘beak’. Indonesian anti-aircraft gunners were ordered to shoot down the next aircraft that overflew them, this they did.

However, it was an Indonesian C-130 with about a company of RPKAD on board who were to jump into the airfield, the gunners’ shooting was good, the RPKAD jumped but the aircraft was losing height and many parachutes didn’t have the height to fully open and the aircraft crashed close to the airfield.

The naval presence comprised minesweepers and other light craft patrolling coastal waters and some large inland waterways, and a 'guardship' (frigate or destroyer) at Tawau. Army vessels, typically 'ramp powered lighters', supported bases on navigable waterways. Hovercraft were also used.

During the year Indonesian forces increased in strength and incursions were increasingly by regular troops, sometimes led by officers trained by the UK. A US Army training team remained in Indonesia throughout the period but does not seem to have had any tactical impact in Kalimantan, although US-equipped Indonesian units appeared there.

Troops facing Kuching were reinforced and in the east amphibious activities increased and TAG’s communications jammed. Moreover, within Sarawak the CCO was expanding and the Borneo Communist Party started producing grenades and shotguns. Total Indonesian forces were:

-

- Facing West Bde — 8 regular and 11 volunteer guerilla companies (companies were up to 200 strong)

- Facing Central Bde — 6 regular and 3 volunteer companies

- Facing East Bde — 4 or 5 KKO and 3 volunteer companies.[24]

However, the initiative remained with Indonesian forces as to where and when they attacked. DOPOPS had repeatedly sought authority for hot pursuit, and even better pre-emptive action across the border. This was denied and some parts of the armed forces considered that a major overt attack on Indonesia would bring the war to a close.

continued below

-

-

continue from above

However, in July the new Labour government approved offensive action across the border, under constraints, conditions of strict secrecy and the codename Claret. However, there was no intention of launching a general offensive or attacks intended to inflict significant Indonesian casualties.

The aim was to keep the Indonesians under pressure and off-balance rather than attempt to pre-empt specific Indonesian attacks, and to this end operations were conducted along the entire length of the border, not just the ‘hot spot’ close to Kuching.[25]

In January reports indicated a large Indonesian force in the 5th Division, in the event a camp of some 60 men was found. Attacked by 11 men of the Royal Leicestershire Regiment they fled leaving 7 dead and half a ton of supplies. In the 1st Division, a force of about 100 crossed the border, apparently heading for Kuching airfield, but they were put to flight by a small force of marines and police. Worryingly, they were well equipped including East European made rocket launchers.[26]

In March in the 2nd Division, 1/10 Gurkhas discovered a force from the 328 Raider Battalion, which were regular Indonesian troops. After being ejected they returned a few weeks later and establish a position in caves in a cliff face. This led to the only use of offensive airpower in the campaign, albeit with approval from London. Wessex helicopters of 845 Naval Air Commando Squadron fired SS11 anti-tank missiles into the caves.[27]

Between March and June a new pattern emerged in the 2nd Division in a series of actions between Gurkhas and professional soldiers from the Indonesian Black Cobra Battalion. However the latter's losses were several times the Gurkhas’ and in one incident 4 Black Cobras clashed with 2 Gurkhas with the Cobras being killed and the Gurkhas remaining unscathed. In another incident 6 Black Cobras were captured by Ibans and lost their heads.

In July there were 34 Indonesian acts of aggression including 13 border incursions in Borneo and there were indicators that Indonesian forces were re-organising.

However, on 16 August armed Indonesian agents were captured in Johore and in the early hours of 17 August a force of about 75 Indonesian Marines and paratroops, with about 25 remnants of the Malayan Chinese Communists, crossed the Malacca Straits by boat and landed south west of Johore. Instead of being greeted as liberators they bumped into the Malaysian Army and most of the invaders were killed or captured in a few days.

However, in the last three months of the year the number of cross border incursions in Borneo dropped significantly.

On 2 September, paratroopers jumped into Labis, Johore, about 100 miles north of Singapore, four C-130 had left Jakarta, only two reached their target and electric storms caused the drop to be dispersed.

They landed close to 1/10 Gurkhas, who were joined by 1st Battalion, Royal New Zealand Infantry Regiment (1 RNZIR) stationed near Malacca with 28 (Commonwealth) Brigade. Operations were commanded by 4 Malaysian Brigade but it took a month to round up or kill the 96 invaders.

Then on 29 October, 52 soldiers landed near the mouth of the Kesang River on the Johore-Malacca border and not far from 28 (Commonwealth) Brigade base at Camp Terendak, Malacca.

The Commanding officer of 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (3 RAR) was given the task of dealing with the invaders with his D Company, B Company 1 RNZIR and C Squadron 4th Royal Tank Regiment with fire support from 102 Battery Royal Australian Artillery. 20 surrendered,[28] others killed and evaders captured by the Royal Malay Regiment.

Indonesian troopers captured and under guard by Malaysian Police 1964

In the same period about 30 landed near Pontian and were hunted down by 1 RNZIR, the Malaysian Army and Royal Federations Malay States Police Field Force personnel in Batu 20 Muar, Johore.[29] There were also terrorist attacks in Singapore.

These attacks on West Malaysia led UK to planning offensive air and sea operations against Indonesia. It appears that Far East HQ produced a tentative list of seven potential targets for retaliation based on four criteria. The criteria were that: the target must be related to the Indonesian attack; must be militarily useful; would produce minimum casualties; and, be least likely to produce escalation.[30]

Indonesian Air Force Tu-16 : 1962

In late 1963 and into 1964 the Indonesian Air Force had taken to ‘buzzing’ towns in Sarawak. This led to Malaysia declaring an Air Defense Identification Zone on 24 February. The RAF started periodic fighter patrols along the border using aircraft such as Javelin and RN Sea Vixens from the fleet carrier in theatre. UK already had 12 Light Air Defence Regiment Royal Artillery (12 Lt AD Regt) stationed in West Malaysia.

In June, 111 Light Anti Aircraft Battery Royal Australian Artillery with Bofors 40/60 guns deployed from Australia to RAAF Butterworth near Penang close to the Thai border. In September, 22 Lt AD Regt with two batteries arrived from UK to defend RAF Changi and Seletar in Singapore, and 11 Lt AD Battery of 34 Lt AD Regt arrived to defend Kuching airfield with batteries rotated through Kuching for the next two years. All the UK batteries were equipped with Bofors 40/70 guns and FCE 7 Yellow Fever.

The year ended with UK Government approving deployment of UK based units from Army Strategic Command and a major reorganisation of Indonesian forces in Kalimantan. However, Sukarno was coming under increasing influence of the Indonesian Communist party (PKI), causing unhappiness in the Indonesian Armed Forces